Last week, Mirabelle Jones and I organised the latest iteration of our—somewhat experimental and, some might say, risky—workshop study series, in which we invite Python novices and aficionados to finetune (i.e., create) their own version of GPT-3, based on their own social media posts and messages. We did so at the beautiful AI Pioneer Center of the University of Copenhagen.

Some of you may remember GPT-3 from the summer of 2021—now considered ages ago in AI-terms—as one of OpenAI’s so-called large language models (LLM). In fact, at the time, it was one of the most advanced models out there (now, it has already been surpassed by a number of newer versions, most notably ChatGPT and GPT-4). While GPT-3 has existed since 2020, it was in 2021 that OpenAI had made finetuning GPT-3 available to anyone with an OpenAI account.

Finetuning, as the word implies, comes down to the molding and adapting of an existing LLM to more accurately reflect certain characteristics of a finetuning dataset. For example, generic LLMs face criticism because—having been built on normative, homogeneous datasets—they tend to misrepresent or be insensitive to minorities (whose data usually are underrepresented in the training datasets). Why, you might ask, are we not using ChatGPT? Unfortunately, the newer versions of GPT are not open to finetuning. Hopefully this might still become possible in the near future.

Our aim for the workshop study was to teach others how to create a personalized ‘chatbot’ based on their own social media texts. Once participants have their personal LLM, my specific angle of interest was to see if there are any insights they might glean from chatting with this potential window into their online personas.

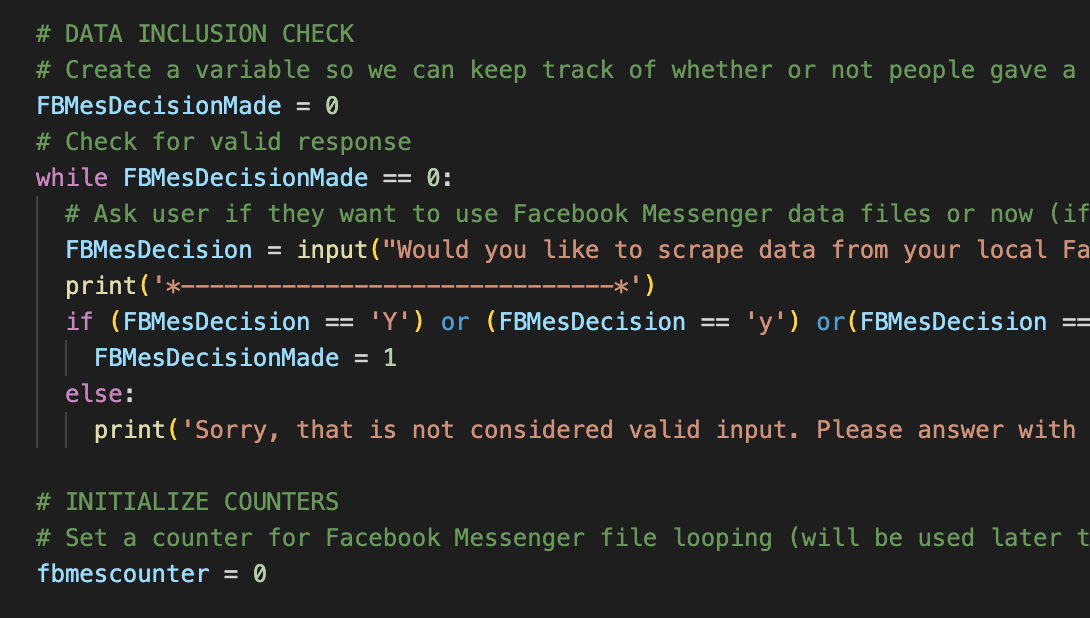

Having run two earlier versions, we decided for this iteration to include an in-person aspect, and this was by far the best approach for the level of intensity and time this workshop requires. We had also made significant improvements to the process since the previous iteration (e.g., going from participants manually assembling their finetuning dataset to using my improvised scraper script).

However, as is always the case with hands-on activities: be prepared to face the unexpected. Multiple ✨exciting new errors✨ popped up that I hadn’t encountered before when using the scraper script—some of which we were able to troubleshoot on the spot, while others could not be solved within the timeframe we had. Fortunately, we had some wonderfully patient and engaged participants in our groups, and thanks to them, we learned a lot!

Based on the last two workshops in Copenhagen, we are planning on improving our process, and I will definitely be making changes to the script to ensure an even better and smoother result the next time. Mirabelle and I both look forward to inviting even more curious minds to our next iteration of GPT finetuning workshops, which will take place in the Netherlands.