Technology, like art, is a soaring exercise

Daniel Bell — The WINDING PASSAGE

of the human imagination.

In addition to the out-there projects I love to engage in on the side, I deeply enjoy helping other teams with research and/or design challenges, especially around technology and wellbeing. Through Studio Gryphire, which consists of a Design and a Research division—although the two may well often combine in a delicious swirl of goodness—I provide freelance services in both of these areas.

At the core of Studio Gryphire lies ensuring that human flourishing and wellbeing are supported. That is why in both my design ánd my research work I focus on projects that relate to human wellbeing and aim to—either directly or indirectly—augment and support the human experience. That is the heart of Studio Gryphire.

Interested in what I can do for you?

Design for Good

In my design work I support teams, companies and individuals with graphic and digital product design. Through my experience creating and designing both graphic material as well as user experiences, my aim is to ensure the intended message or experience reaches its destination. Looking for a logo, illustrations, a refreshed brand identity? Or are you developing an app or game for which you want to ensure human-centric, evidence-based design? I’m your gal.

Research for Good

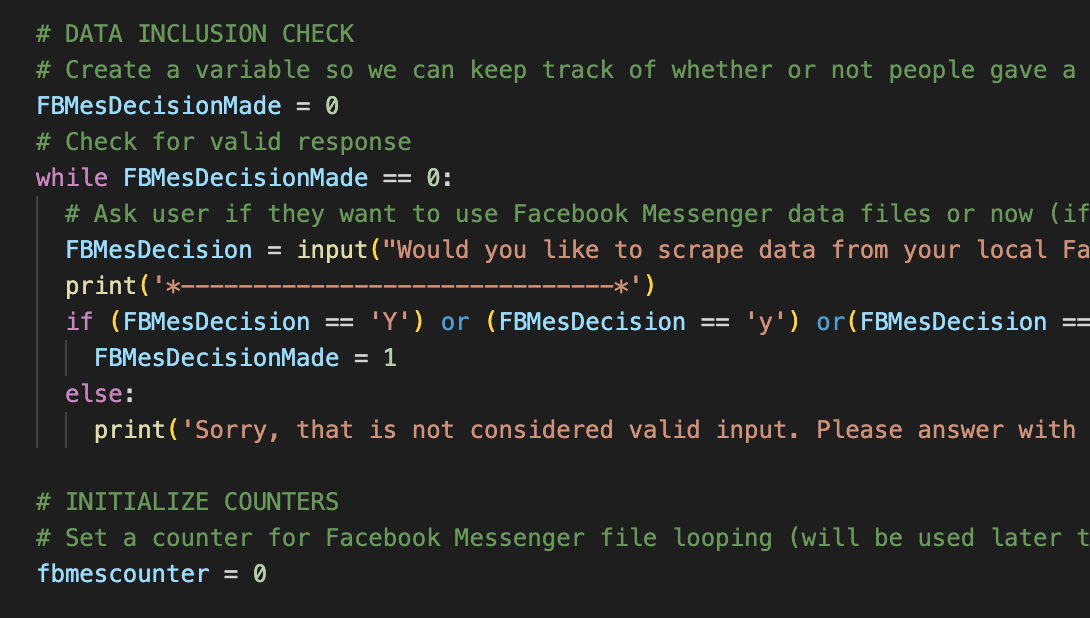

Much like with my design work, the research support I provide for project teams, institutes and organizations varies vastly depending on needs and goals. With my expertise in a wide range of research methods and analytics, I help projects that aim to support human flourishing build a strong scientific and UX evidence-base for their product. My work ranges from literature research and study design to UX research execution, analysis, and beyond.

STUDIO GRYPHIRE

KvK / Chamber of Commerce No.: 90237234

Arnhem | Netherlands